I created a short flash sequence illustrating arcs in head turns..

Head Turn from emma hardy on Vimeo.

Monday, 29 November 2010

Thursday, 25 November 2010

Follow through and overlapping action

The principle of follow through and overlapping action is there to really bring forward the 'believability' of the characters movement.

The principle is dictated to by the laws of physics and follows them as much as it can; follow through demonstrates this the most with it being the law that as a character makes a movement, any loose items such as hair or an item of loose clothing will continue moving once that character has stopped due to the 'drag' on the item.

Overlapping action is simply a second action that runs at a different time alongside another action or movement. A good example of this is a walk cycle, where the arms are moving at a different time to the body and legs and therefore 'overlap' the action.

Examples:

This short walk cycle demonstrates overlapping and secondary action in the characters movement.

Look how a simple standard walk is made more realistic with the simple addition of this principle; the overlapping action of the arms and follow through of the floppy ears give a real sense of weight to the character and show off his features.

Links:

Fig. 1 and 2: http://www.animationbrain.com/follow-through-overlapping-2d-animation-principle.html

Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajagVS-M7b0

The principle is dictated to by the laws of physics and follows them as much as it can; follow through demonstrates this the most with it being the law that as a character makes a movement, any loose items such as hair or an item of loose clothing will continue moving once that character has stopped due to the 'drag' on the item.

Overlapping action is simply a second action that runs at a different time alongside another action or movement. A good example of this is a walk cycle, where the arms are moving at a different time to the body and legs and therefore 'overlap' the action.

Examples:

| Fig. 1 |

The simple follow through action of the hand continuing after the throw as it slows down displays the laws of physics and keeps the piece from becoming static, therefore making the whole action more realistic and enjoyable.

| Fig. 2 |

Notice how the simple addition of the skirt to a bouncing ball gives it more meaning and sense of being. It adds more reference to the laws of physics by introducing the air resistance or 'drag' on the skirt and makes it more believable.

This short walk cycle demonstrates overlapping and secondary action in the characters movement.

Look how a simple standard walk is made more realistic with the simple addition of this principle; the overlapping action of the arms and follow through of the floppy ears give a real sense of weight to the character and show off his features.

Links:

Fig. 1 and 2: http://www.animationbrain.com/follow-through-overlapping-2d-animation-principle.html

Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajagVS-M7b0

Labels:

Appeal,

drag,

exaggeration,

Follow through,

Overlapping action,

walk,

walk cycle,

weight

Tuesday, 23 November 2010

Timing - Initial Research

Timing can have a dramatic effect on the look and feel of an animated scene. The lengthening or shortening of poses, the amount of inbetweens, the spacing, all of these affect timing.

To start with, I am going to look at Disney's 'The Illusion of Life':

When talking about timing (p64/5), the authors, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, give a great example of just how the much of an effect on the movement the timing of inbetweens can have.

Talking about two drawings of a head, 'the first showing it leaning toward the right shoulder and the second with it over the left and its chin slightly raised.' (p64), they state how large a 'multitude of ideas' the inbetweens can communicate:

To start with, I am going to look at Disney's 'The Illusion of Life':

When talking about timing (p64/5), the authors, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, give a great example of just how the much of an effect on the movement the timing of inbetweens can have.

Talking about two drawings of a head, 'the first showing it leaning toward the right shoulder and the second with it over the left and its chin slightly raised.' (p64), they state how large a 'multitude of ideas' the inbetweens can communicate:

No inbetweens - The character has been hit by a tremendous force. His head is nearly snapped off.

One inbetween - . . . has been hit by a brick, rolling pin, frying pan.

Two inbetweens - . . . has a nervous tic, a muscle spasm, an uncontrollable twitch.

Three inbetweens - . . . is dodging the brick, rolling pan, frying pan.

Four inbetweens - . . . is giving a crisp order, "Get going!" "Move it!"

Five inbetweens - . . . is more friendly, "Over here" "Come on-- hurry"

Six inbetweens - . . . sees a good-looking girl, or the sports car he has always wanted.

Seven inbetweens - . . . tries to get a better look at something.

Eight inbetweens - . . . searches for the peanut butter on the kitchen shelf.

Nine inbetweens - . . . appraises, considering thoughtfully.

Ten inbetweens - . . . stretches a sore muscle.This perfectly illustrates how much a matter of inbetweens can affect the movement of a character. Within nine frames, a character could have gone from being hit by brick, to instead stretching a sore muscle.

Anticipation - Initial Research

Anticipation within animation refers to a small movement that prepares for the main action that is about to follow. For example, bending the knees slightly before a jump. Anticipation is used for a variety of reasons, one being that it allows the viewer to understand rapid movement better, such as a character preparing to run and then dashing off screen. This method is also used to help portray weight or age within the character, a heavy person may place their hands on their knees before sitting up from a chair, whereas a lighter person may spring up without much anticipation of movement.

image source: http://www.google.co.uk/imgres?imgurl=http://lh3.ggpht.com/_jL0PYTVd-Zs/SwiH94QfXQI/AAAAAAAACos/fErgDWOd-lA/s800/m03_s03_Antic.jpg&imgrefurl=http://forums.awn.com/showthread.php%3Ft%3D12412&usg=__7sTdUmAHlGSnSdoqaLjHYCk

K0q4=&h=373&w=500&sz=94&hl=en&start=193&sig2=wvKmGeRplfNHFyqlSm3AKA&zoom=0&tbnid=-anega2Fg98IcM:&tbnh=97&tbnw=130&ei=z2TsTKX7ApiG4gbVzfDCAQ&prev=/images%3Fq%3Danticipation%

2Bin%2Banimation%26um%3D1%26hl%3Den%26client%3Dsafari%26rls%3Den%26biw%3D1280%26bih%3D664%26tbs%3Disch:10%2

C5920&um=1&itbs=1&iact=rc&dur=479&oei=nGTsTM3rFMqxhAf3qNnNDA&esq=11&page=12&ndsp=15&ved=1t:429,r:8,s:193&tx=33&ty

=14&biw=1280&bih=664

Below is student sequence found on youtube, illustrating some anticipation within animation.

Sunday, 21 November 2010

Appeal - Research

Appeal is what helps animation characters seem "real" and interesting . It can be likened to "charisma" in an actor. Appeal is not restricted to sympathetic, beautiful characters, or protagonists; villains or monsters should have their own appeal too. The important thing is that the character has its own personality and the viewer is stimulated by it in some way, instead of bored. Appeal can rely on many aspects of animation - story, impressive visuals, sounds and character development, to name a few.

In characters that are intended to seem "good" or likeable, symmetry is often used. This is because we as viewers are often attracted to symmetry and idealised proportions, which make a character seem more "perfect" in our eyes. The same applies to the use of "baby-faces," as we tend to find babies innocent and cute, which adds likeability to a character when used. Disney and anime cartoons that makes use of the "super deformed" style, use of this cute, "baby-face" technique to make viewers feel more sympathetic towards the characters.

However, it is often considered unappealing to use something known as "twins" in an animation, meaning when both arms or legs are doing the same thing, creating a stiff, unnatural position that makes a character seem less "real." Introducing some "noise" to the geometry or design of a character can sometimes add to appeal.

Below: Super-deformed anime style makes characters seem more cute and "appealing" to the audience, as well as gives a more light-hearted, humorous take on emotions:

Lack of "solid drawing" often detracts from appeal, also. A strongly appealing character should have high quality design, drawing, modelling, poses and animation, expressed cleanly and clearly. Anything overly complicated and difficult to read, or clumsy and awkwardly moving lacks appeal to an audience.

Below: Example of a clumsy, unappealing character on the left, and strong but simple appealing characters on the right.

Below is a video I found explaining how to create appeal in a character's posing; although fairly technical I think this is quite helpful as the author talks through his thinking around the character's pose and how he is using it to display a certain emotion.

References

Willian (2006). "Appeal" [Online] Blender. http://wiki.blender.org/index.php/Doc:Tutorials/Animation/BSoD/Principles_of_Animation/Principles/Appeal (accessed 21 Nov 2010)

"Appeal" [Online] http://www.evl.uic.edu/ralph/508S99/appeal.html (accessed 21 Nov 2010)

Thursday, 18 November 2010

Staging: Initial Research

Staging and composition play a huge part in the animation process, brought into development during the early stages during storyboard, through to layout, animation and tweaked again during the final edit. Staging can make all the difference in the meaning and effectiveness of a shot, helping it to communicate the desired emotion or reaction.

Here I am starting initial research by looking generally at how staging has been used in animated films and series, briefly looking at the basics of staging and how they are applied.

Hanna Barbera

Staging plays a very important part in a lot of Hanna Barbera cartoons because, due to the highly stylised aesthetic and limited animation technique, the composition of the frame is vital in helping to quickly and effectively communicate the intentions of the scene.

Here I am starting initial research by looking generally at how staging has been used in animated films and series, briefly looking at the basics of staging and how they are applied.

Hanna Barbera

Staging plays a very important part in a lot of Hanna Barbera cartoons because, due to the highly stylised aesthetic and limited animation technique, the composition of the frame is vital in helping to quickly and effectively communicate the intentions of the scene.

Here you can see how the shots are staged for maximum effect. As

Huckleberry Hound enters the frame, the camera cuts in close to allow for

a more intimate audience interaction, and creates a tight angle, setting

it up for the payoff, as Huckleberry falls down the crater, maximising

the comic effect.

Disney

In contrast to the simple and deliberate staging of the Hanna Barbera cartoons, Disney employs a more subtle, and cinematic approach to the staging, as opposed to Hanna Barbera's economic and time-effective compositions and character positioning.

Here you can immediately see the cinematic power of the staging

employed here by the disney layout artists. The sweeping dunes of Aladdin

provide a significant contrast to the relatively tiny characters in the foreground,

helping to create a huge sense of scale and prowess. Had the shot been staged

with the characters much closer in the foreground, the perspective and scale

would have been lost.

Wednesday, 17 November 2010

Secondary Action - Research

In every animation scene there is a primary action, intended to get a certain point across. For example, the primary action in a walk-cycle is the character walking. Sometimes however, more emphasis is put on the primary action using one or more secondary actions that result directly from the primary action. In a walk cycle for example, a secondary action could be the character swinging his arms or expressing an emotion using facial expressions. Use of secondary action in a scene often gives more life and dimension to a movement or character.

Example of a Secondary Action - the primary action is the swinging of the pendulum, the secondary action is the movement of the "tail":

An important rule about secondary action is that it should not dominate or detract attention away from the primary action. If this is the case, the secondary action is most likely wrong for that particular scene, or staged incorrectly.

There are dangers involved with using facial expression as a secondary action, in that these subtle expressions may not be noticed by the viewer when combined with a dramatic movement. It is often considered better to include facial movement at the beginning or end of a greater movement, rather than during. In some scenes the facial expression may be the primary action, in which case the secondary actions must be carefully planned around it so they do not detract from it. In other scenes, the facial expression may be used as a secondary action, in which case it should be staged so that it's obvious and visible to the viewer, yet isn't dominating the primary action.

Example of facial expressions as primary action with carefully placed secondary actions that don't detract from the focal point:

A reccommended way of making sure any secondary actions remain subordinate to the primary actions is:

References:

De Stefano, Ralph A. "Secondary Action". [Online] Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago. http://www.evl.uic.edu/ralph/508S99/secondar.html. (accessed 17 Nov 2010)

"Flash Animation Tutorials - Secondary Actions" [Online] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yUSOBD4igc (accessed Nov 17 2010)

Example of a Secondary Action - the primary action is the swinging of the pendulum, the secondary action is the movement of the "tail":

An important rule about secondary action is that it should not dominate or detract attention away from the primary action. If this is the case, the secondary action is most likely wrong for that particular scene, or staged incorrectly.

There are dangers involved with using facial expression as a secondary action, in that these subtle expressions may not be noticed by the viewer when combined with a dramatic movement. It is often considered better to include facial movement at the beginning or end of a greater movement, rather than during. In some scenes the facial expression may be the primary action, in which case the secondary actions must be carefully planned around it so they do not detract from it. In other scenes, the facial expression may be used as a secondary action, in which case it should be staged so that it's obvious and visible to the viewer, yet isn't dominating the primary action.

Example of facial expressions as primary action with carefully placed secondary actions that don't detract from the focal point:

A reccommended way of making sure any secondary actions remain subordinate to the primary actions is:

(Quoted from an article found at http://www.animationbrain.com/secondary-action-2d-animation-principle.html)

the way you want it.

action, making sure that it all works the way you want it to. And that it

doesn’t overwhelm or detract from the primary action in any way.

animation relates to the primary and secondary actions the way they should.

References:

De Stefano, Ralph A. "Secondary Action". [Online] Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois at Chicago. http://www.evl.uic.edu/ralph/508S99/secondar.html. (accessed 17 Nov 2010)

"Flash Animation Tutorials - Secondary Actions" [Online] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yUSOBD4igc (accessed Nov 17 2010)

Tuesday, 16 November 2010

Arcs - Animation Principles

Arcs are in most movement that we encounter in day to day life as most naturalistic action follows a series of curves and arcs; very few natural actions are linear, the majority of such action occurs in more mechanical situations.

Because of this arcs must be incorporated into animated action in order to sustain believability. However sometimes animators may choose to disregard this approach, in order to create more emphasis on the keys rather than the movement. John Kricfalusi did this when producing "Ren and Stimpey" creating more snappy action.

Using an arc within your animation movement essentially means that the action follows a curve of action rather going in a straight line.

An example of arcs used in animation:

An example of animation ignoring the arcs approach:

I intend to produce my own short line tests illustrating this approach further, alongside more in depth research.

References:

"Animation the Mechanics of Motion" Chris Webster. Pages 50-5

"Animators Survival Kit" Richard Williams. Pages 90-2

Monday, 15 November 2010

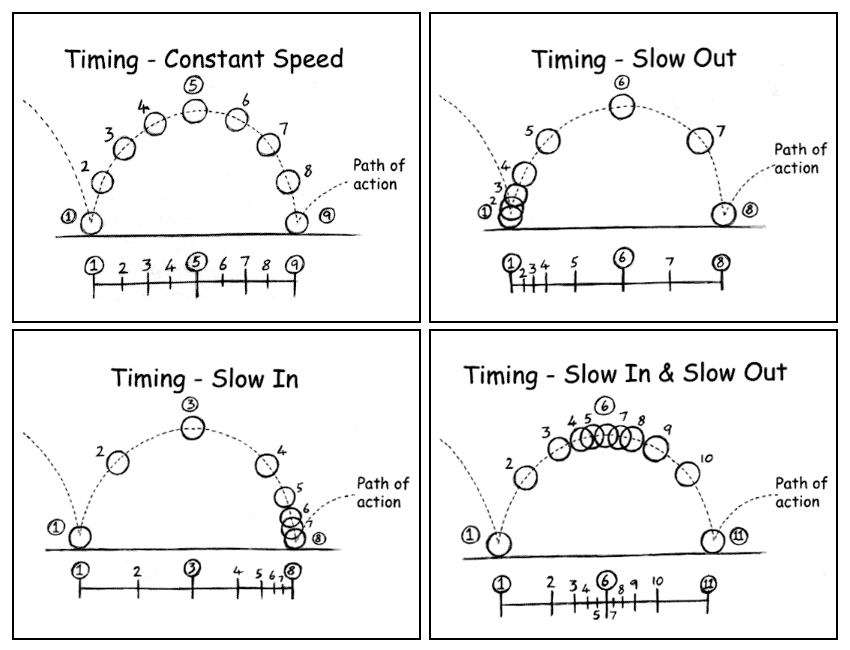

Slow in and Slow Out - Research

Slow in and slow out comes from the fact that certain movements need time to accelerate and decelerate, such as movements made by the human body and even inanimate objects such as bouncing balls.

Therefore the movement is slowed down by the use of more frames at the beginning and end of the action and less frames in the middle of the action.

I intend to find more examples of this and come up with my own but here are the initial examples I have found:

http://sapitt.com/blog/113/principles-of-animation-slow-in-slow-out/

http://profspevack.com/archive/animation/course_cal/week13/week13.html

Therefore the movement is slowed down by the use of more frames at the beginning and end of the action and less frames in the middle of the action.

I intend to find more examples of this and come up with my own but here are the initial examples I have found:

http://sapitt.com/blog/113/principles-of-animation-slow-in-slow-out/

http://profspevack.com/archive/animation/course_cal/week13/week13.html

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)